Papers

Working Papers

Wealth and Intergenerational Political Power Mobility

@unpublished{praninskas2025wealth,

author = {Praninskas, Gailius and Munroe, Ellen},

title = {Wealth and Intergenerational Political Power Mobility},

year = {2025},

note = {Working Paper}

}

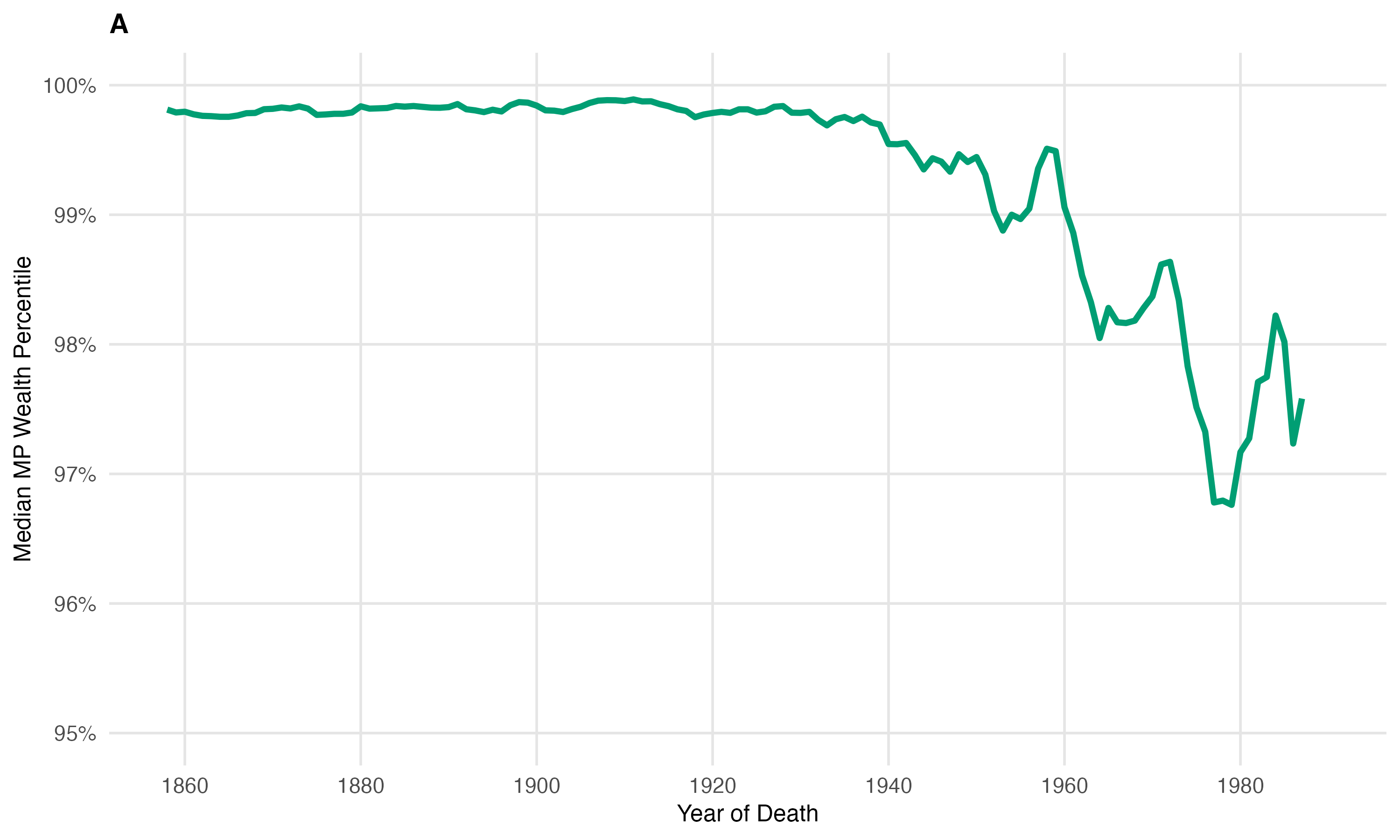

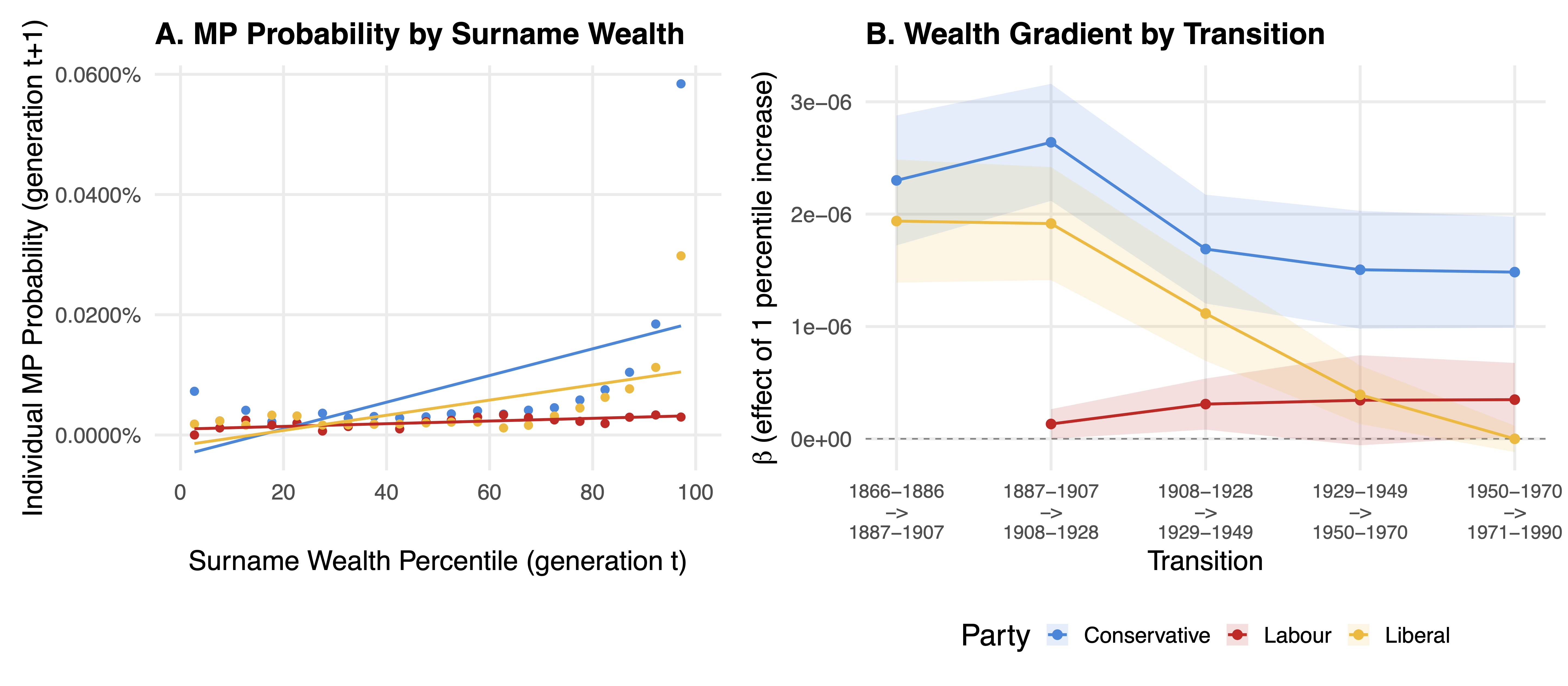

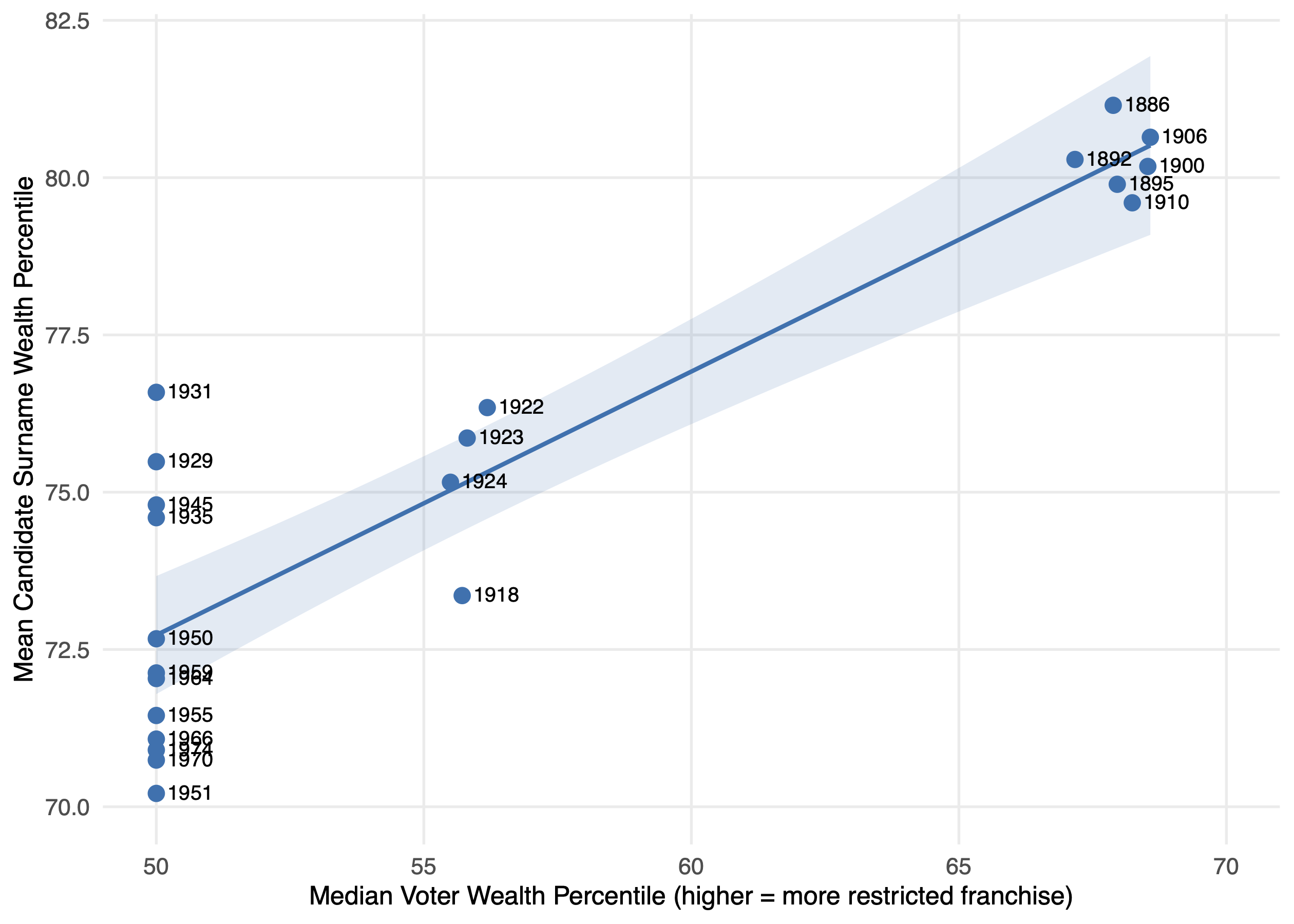

We provide a comprehensive account of the intergenerational relationship between individual wealth and political power over 133 years of democratization. Combining the biographical records of members of parliament (MPs) and other elite individuals in England and Wales with 17 million individual-level wealth-at-death (probate) records from 1858 to 1990, we establish four main facts. First, we find that the politically powerful are much wealthier than the average person, although this gap has narrowed in time. The median wealth-at-death percentile of MPs fell from above the 99.9th percentile in 1858 to the 97.5th percentile in 1990. Second, this pattern is largely driven by a declining share of entrants from extremely wealthy families. Using a surname-level analysis, we find that being at the very top of the wealth distribution is highly predictive of political entry, and that most gains in power mobility have occurred among upper-middle wealth surnames at the expense of the wealthiest. Third, we investigate the mechanisms behind this decline. The wealth advantage operated primarily through candidate selection rather than electoral success: the gap between candidates and the population was six times larger than the gap between winners and losers. Franchise expansion contributed to this transformation—under restricted franchise, the marginal effect of wealth on political entry was approximately ten times larger than under universal suffrage. Fourth, wealth matters not only for entering politics but also for sustaining political dynasties within families. Even within MPs, wealthier individuals see more of their descendants enter parliament and this effect persists after controlling for ancestral dynasties, education, career success, and social background. Exploiting quasi-random variation in estate tax incidence around regime changes, we show that this relationship is causal: inheritance taxation reduces dynastic persistence. Over our period of study, democratization substantially weakened but did not fully eliminate the relationship between dynastic wealth and political power.

- Danish Historical Political Economy Workshop (2025)

- Royal Economic Society Annual Conference (2025)

- 14th Annual Lithuanian Conference on Economic Research (2025)

- Warwick-LSE Political Economy PhD Conference (2025)

- Oxford University Political Economy Work in Progress (2025)

- LSE Political Science Political Economy Work in Progress (2025)

- LSE SPEECH (2024, 2025)

- LSE Workshop on Institutions and Political Economy (2024)

Key Findings

▶

1. MPs have become less wealthy over time, but remain far richer than average

The median MP's wealth-at-death fell from the 99.9th percentile in 1858 to the 97.5th percentile by 1990. While democratization narrowed the gap, MPs remain substantially wealthier than the population they represent—even today's politicians come from the top few percent of the wealth distribution.

▶

2. This is largely driven by selection from wealthy families

Individuals from the wealthiest surnames were over 25 times more likely to become MPs than those from ordinary backgrounds. This pattern varied by party: Conservatives and Liberals drew from the very top of the wealth distribution, while Labour MPs, though less wealthy, still came from well above the population median. Over time, the wealth gradient declined for both the Conservatives and the Liberals.

▶

3. Democratic and economic institutions reduced the influence of wealth

Two types of institutional change weakened the link between wealth and political power. Franchise expansion brought in voters who were less likely to favour wealthy candidates: under restricted franchise, wealth's effect on political entry was roughly ten times larger than under universal suffrage. Inheritance taxation reduced the dynastic transmission of both wealth and political power: higher estate taxes caused descendants to spend less time in Parliament. Progressive taxation promotes not only economic equality but also political equality.

Work in Progress

Privatising Common Property: Evidence from the Welsh Parliamentary Enclosures

Economics literature stresses the importance of well-defined, private property rights for efficiency and development. However, the economic impact of transitions from communal to private ownership remains poorly understood. We construct a novel dataset from historical records to investigate this within the context of the Welsh Parliamentary Enclosures, a series of parliamentary acts spanning 1760–1936 that transferred communally-owned or managed land to sole proprietorship. The analysis presents four findings: (1) contrary to a common historical narrative that enclosures reduced population, there is no evidence of this in Wales, (2) there was no significant change in farming occupations post-enclosure, again contrary to a historical narrative, (3) enclosure did not correlate with grain market prices in Wales, and (4) surprisingly, parishes post-enclosure have significantly lower land value and lower land ownership concentration relative to an unenclosed control group. We explain our findings in light of issues stemming from creating many fragmented land holdings, which generate hold-up and other contracting problems.

Wealth is Health: Public Healthcare and the Longevity Gradient in England and Wales 1858–1995

How does wealth affect life expectancy, and what reduces this inequality? We measure the wealth-longevity gradient using yearly individual-level data in England and Wales from 1858–1995 and examine how it changed with the expansion of public healthcare, focusing particularly on the introduction of the NHS and the rollout of public hospitals. We also explore how this relationship differs over time and by gender, with particular attention to maternal mortality where wealth inequalities translate most sharply into survival differences, and where access to healthcare is especially critical. Understanding what flattened the gradient matters for understanding how introducing public health care systems reduce inequalities. For low- and middle-income countries building healthcare systems today, where policymakers face similar choices about public versus private provision with limited evidence on distributional impacts.